Double Penis

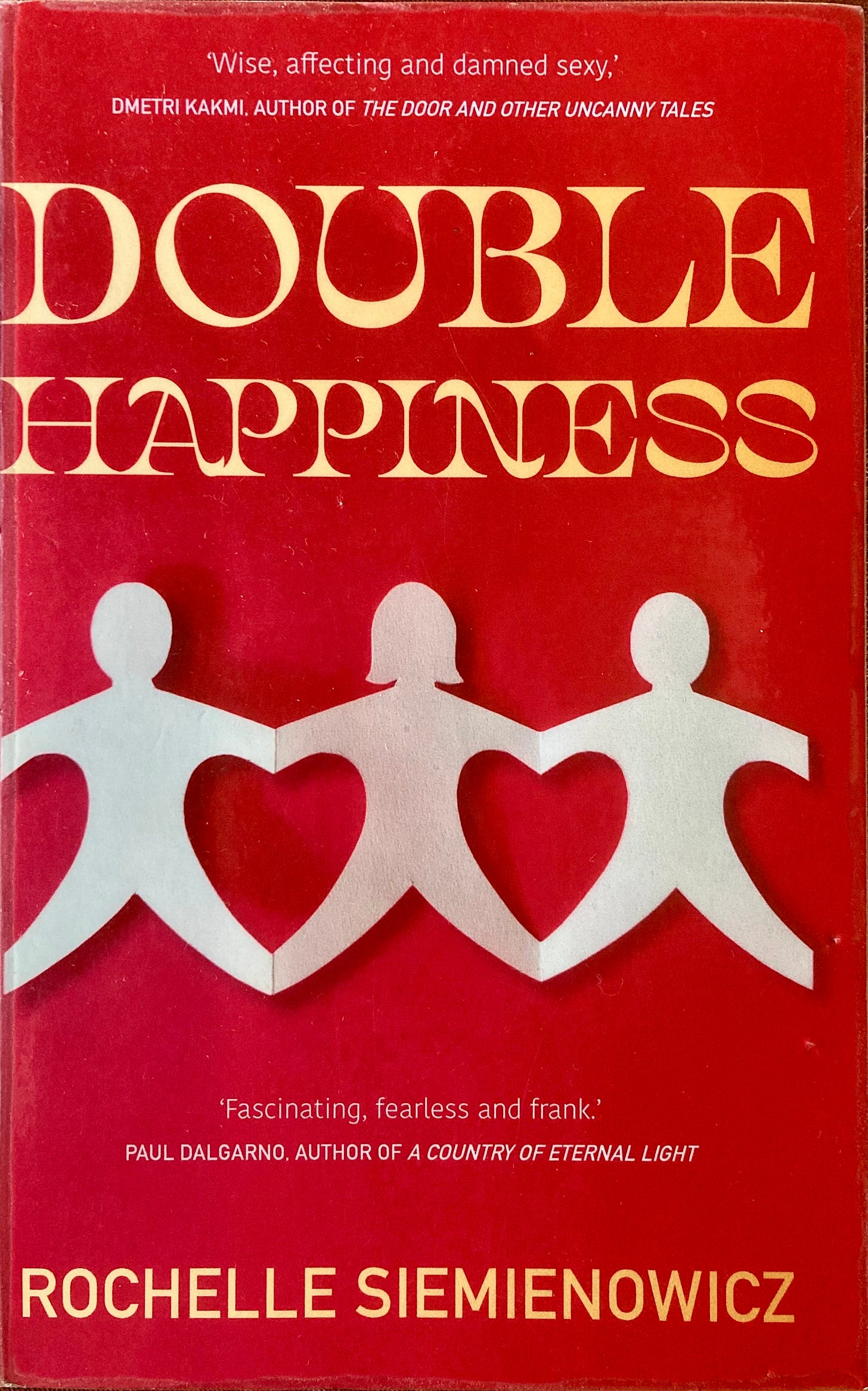

Review of Double Happiness by Rochelle Siemienowicz (MidnightSun, Adelaide 2024)

Headnote: this piece is replete with spoilers. I write assuming that you have either read the book or do not care about the spoilers. I do encourage you to go to the book, whether you read this article or not. It is a powerful work dealing with intricate emotional issues that had me thinking and rethinking, exploring and wondering. And what else could one ask for from a novel?

After a period of erotic infidelity some years prior and, having suffered the fallout of the breakup with her secret lover, Anna has been back in the warmth and safety of her monogamous marriage to husband Brendan for some years. They live together—she a journalist, he an academic—in inner city Melbourne, with their 12 year old son, Luka.

We meet Anna in the early pages of Double Happiness. She is at a conference where she encounters an attractive man—Jeremy. She is engaged by his non-leering, non-desperate manner, which helps hold down the temperature between them, even if she knows that what she really wants to do, and will eventually do, is fuck him.

She succeeds in holding-off for a few weeks before succumbing to her desires, which are so intense that she comes to orgasm almost immediately into their first love-making session. After that they begin to see each other regularly, she returning home after the passionate encounters to her normal married life with husband and son, silently dealing with the cold hard feelings of guilt and despair at her deception and at her breaking of her pledge to herself to desist from following her desires. And something important has happened: this is more than a casual affair, it is a connection that will lead very quickly to ‘love’. After barely three months she and Jeremy declare to each other: ‘I love you, I love you’.

However the deception is ever present. As they negotiate their own relationship, it exists in the shadow of Anna and Brendan’s marriage. They are faced with the standard choices: continue a clandestine affair, break up the marriage or end the affair. Destroying the marriage is not an option—Anna does not want this and Jeremy also refuses to be the agent of its destruction.

But even as their relationship flourishes within the bubble of their stolen time together, tension and discomfort mount. This is skilfully held back by Siemienowicz, until one evening after ten months, sitting in front of the television, apparently unbidden, Anna confesses the affair to Brendan. It is the scene, as she says: ‘required in any version of the grand old story of infidelity. The revelation.’

Brendan is deeply hurt by her actions—so many years of stable loving marriage unexpectedly blown apart by a few short sentences. Tearful, tormented, angry, he stomps about the house as he tries to come to terms with his—and his family’s—new reality. His violence is contained, but self-pity, sadness and fear are awash within him.

Over and over she tells him how much she loves him, all the while expecting to be told to leave the house. He says that she must do what she wants, like she always does.

A few hours later they lie in bed, he demanding more information from her even as every bit hurts him; she carefully manages her words, trying to reduce the pain they inflict.

‘You’re not going to give him up, are you?’ There was horror in his voice. ‘And if I ask you to choose, you’ll choose him, won’t you?’

‘I don’t want to choose,’ she said.

‘Then what am I supposed to do?’ He moved away from her and buried his head in his pillow. ‘I feel sick. Sick.’ He groaned.

She moved closer and kissed his neck. ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry,’ she whispered ‘I’ve fucked up so badly. But I love you. Please don’t hate me.’

‘That’s the problem, isn’t it?’ He was crying. ‘You make me sick, but how can I possibly hate you when I love you so much?’

She lifted herself up and covered him with her body, kissing his wet face, holding it in her hands so she could kiss it all over, pressing herself into him until he softened and took her into his arms. She could feel him hard against her thigh, a contradictory mix of lust and anguish.

Then she was fucking him, as if their life together depended on it, trying to tell him with her body that she hadn’t left, she wouldn’t leave, unless he made her.

Afterwards, when they were lying side by side in the grey dawn, with no part of their bodies touching, he said gently, ‘What are we supposed to do now?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘What have you done to us, Anna? What have you done?’

We arrive at the core of the narrative. Anna refuses the standard choices: she wants to keep her marriage and she wants to keep her new lover. She believes that she can make new arrangements which will allow her to share herself—as a lover, a companion, a domestic partner, a mother— loving both men and having them both love her. It’s based on a belief that a person can love more than one person at a time, and that stable relationships can be created as long as the love is ethical and neither monogamous nor exclusionary. This arrangement includes the possibility, maybe the desirability, even the necessity, that the two men will take other lovers as well.

Anna’s actions—her determined pursuit of her desires and the passion which bursts through in the writing—demand that readers reflect on how we see the family unit, in both traditional and non-traditional forms. The book’s ideas are located in the open, ‘progressive’ communities in the ‘West’, where orthodox monogamous marriage is increasingly under the spotlight, where the recipes for ethical non-monogamy—like polyamory—are being proposed as alternatives to the limitations and clear failures of the traditional models. Double Happiness is a powerful exploration of these ideas. The main character’s strength, born of her struggles as a woman caught between her desires and the societal norms, gives her the confidence and ability not only to imagine a new configuration but to risk so much to try to implement it.

And, having said that with much admiration, I felt (and still feel) not a little uncomfortable and was left with questions, both of the novel and of its core ideas.

Brendan is portrayed as someone with an enquiring mind, a man who values ideas and seeks understandings of the political and theoretical currents in the world—qualities that Anna greatly admires in him. However, from the perspective of adventure, non-conformity, pushing boundaries he is portrayed as staid, reluctant and cautious. And of course it is precisely these limits that Anna defies when she falls in love with Jeremy and will not give him up.

Anna repeatedly insists that she loves Brendan. But, however one may choose to define the word, this is a little difficult to accept given that she was prepared to not only hurt him very profoundly and—after acknowledging that she has fucked up ‘so badly’— that she refuses to try ease his pain by perhaps agreeing to stop seeing Jeremy or at least offering to discuss that possibility. She presents a fait accompli to Brendan (and her son) in the most brutal fashion and can only offer the assurance that she loves them and will continue to do so.

But what does she mean here by love? Clearly differing notions of what love is are at play, according to the contexts. The love we have been witnessing grow and flourish between her and Jeremy is not the love—the passionless, humdrum, married-life kind of love—that she will continue to have and hold for Brendan (and her child, obviously).

Clear, but unsaid, it means that the special quality of emotion that they shared—many of the hopes and aspirations and perspectives on their lives together—have changed; she may still love him, but not in the way the two of them understood the word when accepting the orthodoxies of a monogamous marriage.

The kind of love that Anna proposes to Brendan, take it or leave it, is the love they now have as a married couple of 12 years in suburban Melbourne. She offers him a love stripped of passion and dreams, a love, that, as deep as it may be after so many years together, is more akin to the love she has for her child, a love that many of us are fortunate to know, a love of kith and kin. The difference perhaps is that it does allow for occasional sex and, I suppose, a kind trust and intimacy built over so many years.

But, to my mind, the painful jealousy that Brendan experiences is a pointer indicating that there is more to the married couple version of the love he has for her. And that something is lost, gone. The love she is offering will hurt more than bring joy; it is a love that feeds the stabbing pain of loss, that knows that when she is at home ‘with’ him just as when she is not at home, she is more present to the other.

It is sad. But better perhaps than if she had just walked out the door, with or without their child.

The second half of the book tracks the post revelation developments of Anna’s two relationships. It focusses mainly on the evolving love affair of Anna and Jeremy, and, at times, looks at the fallout and healing between Anna and Brendan. The novelist naturally finds the tussles and joys of the extended drama of love/ non-monogamy/ jealousy between Anna and Jeremy to be far more fertile ground. Anna is, after all, the central character. Recounting her evolving situation—confronting the realities of ethical non-monogamy—is where the real power-writing happens. The passages dealing with Brendan, after the initial shocks are over, are by contrast, generally quite matter of fact.

After she reveals her growing love for Jeremy and while insisting on her desire to remain in the marriage, Brendan does not leave the house nor demand that she go. He takes the pain. Siemienowicz recounts Brendan’s thoughts:

Other husbands would leave, or make her leave, or give her an ultimatum. But who would pay for that? They all would, especially Luka. Every solution was drenched in misery. His own was a given, no matter what he chose, so the only logical option was to calculate the result that would cause the least misery to the most people.

...he could try to accept the situation, run with it, roll with it. Suffer it. ...It was a galling proposition. It made his stomach churn. He wanted to vomit...but it was the only virtuous choice…

Mind over matter; the rational human brain over base material carnality; implacable logic in the face of the flood of pre-rational emotion. Virtuous? Suffer it? Brendan chooses the path of his suffering, because ‘it will cause the least suffering to others.’ Interesting. Self-abnegation as self-interest. Even more interesting when measured up against Anna, who is at the other end of the self-abnegation scale, driven so forcefully as she is by her own needs and desires.

She is delighted—as is Jeremy (after much surprise)—to have been given a green light to follow their passions. Anna knows that she and Brendan have to work through the issues and for him a verbal structure, a network of concepts, are what he needs to master his emotions. She proposes that they visit a counsellor, ‘One who specialises in polyamory’.

While these sessions are important and impactful and do take both characters forward, the words and understandings derived hardly impact on Brendan’s pain.

In a heart-wrenching scene in a restaurant in which Anna, Jeremy and Brendan try to normalise their emotions, Brendan behaves petulantly and, even though aware of his own outrageous conduct, cannot help himself. Siemienowicz writes of Jeremy reflecting on the evening:

(Brendan) could be such a cruel and selfish child. But for all the reassurance they gave him, he (Jeremy) was correct in his assessment. (Brendan had) lost something precious. He was right to feel abandoned. Anna’s commitment was ongoing, but if there was a competition for her passion, Brendan was the loser.

She rounds off Jeremy’s thoughts as follows: ‘If only Brendan could fall in love too.’

Over the course of the second part of the book we see Brendan get involved with another woman, Elke, herself part of a number of polyamorous partnerships. While not exactly a relationship of deep love, in the sense that Anna and Jeremy give to the word, it is close, lasting and seemingly satisfying. Anna likes the fact that he has found Elke—both for his sake but also, I get the sense, because it takes a lot heat off her.

But it is not as if it is a smooth ride for Anna and Jeremy either. Among the most interesting parts of the book for me were attempts by Jeremy to form relationships with other women, to ‘balance’ the fact that Anna has Brendan and other flings here and there. Towards the end of the book he enters into a relationship with Lizzie. At first it seems to have legs and Anna tries her utmost to accept her into the relationship ambit, as is only fitting for a proper ENM set-up. But it does not last; it does not work too smoothly for Jeremy but, more important, Anna cannot stomach it. She is jealous to a point of almost giving up on Jeremy. He cannot manage the strain of hurting both women and decides to give up what he has built with Lizzie.

‘I’ve been thinking a lot about happiness,’ he said. “Lizzie’s not happy.’

Anna quickened at the name, the Pavlovian panic response she needed to master now that the other woman was an ongoing fact.

‘And you’re not happy,’ he continued. ‘And if the two people I care about aren’t happy, then how can I be happy?’ He tried to meet her eyes, but she wouldn’t give him the satisfaction.

...’Making you both unhappy to have what I want —that kinda makes me an arsehole, doesn’t it?’

‘Not entirely.’ She tried to laugh. It was gratifying to hear him struggle.

...’there’s only one solution. I need to break up with her.’

As I say, the latter part of the novel focuses on Anna and Jeremy. It seems to me that from the beginning he would prefer to have Anna to himself, but acquiesces to Anna’s continuing marriage and desire-driven arrangements. This—his preference—is not stated and could well result from me reading too much into the spaces between the lines. After a number of years and failed non-monogamous relationships—particularly the failed attempts with Lizzie—the two of them slip into being with each other, a solid pair of lovers. I believe that the unfolding of the novel in the last ‘movement’ speaks to this reading. And the final pages see Anna and Jeremy portrayed like a couple heading into middling-old age—walking the dog in a cemetery, a monogamous couple in all but name, sporting a few appended relationships and many battle scars.

‘What should we cook when we get home?’ he said…

‘How about toasted cheese sandwiches?’ she said ‘…With loads of butter?’

‘I love the way you think.’ He pulled her into him for a kiss. ‘I love what we have. What we are now.’

Brendan is hardly present in the last chapters of the novel, appearing only in the role of house-husband—the solid pillar and sounding-board to the dramas of Anna’s relationship with Jeremy. This is only to be expected as his situation no longer impacts directly on the core story. He does make a comeback however—in the novel’s Epilogue.

Anna the writer (now hardly distinguishable from the irl writer Rochelle Siemienowicz) ends with Brendan’s comments on the draft of the memoir/novel she has been writing in the latter half of the book:

‘...you’ve made him too nice,’ Brendan says. ‘“Good old [stand in name for Brendan] going along with it all”. You need to put in more of the ugliness, the festering resentment and mistrust in the first years…’

As a reader, my feeling was that Brendan could go harder, much harder. He was treated abysmally—although, arguably, no worse than the many caught in the many fracturing marriages since the beginning of the institution. The ugliness, festering resentment and mistrust he talks about, are here folded into the polyamory story. The pain and jealousy he experiences are an unfortunate fall-out of Anna’s determined plan to build on the love created in the marriage over many years and create around it a collection of non-exclusive intimate relationships. People will suffer; Brendan suffers but so do Anna and Jeremy. But they will all also know joy and happiness, including Brendan who has—admirably, pragmatically—built a new workable life within the new context. He could have gone much harder but we should remember that he choses to stay, choses to find a role for himself in Anna’s and his family’s life.

Double Happiness does not set out to be a map for navigating through the hills and valleys of ethical non-monogamy and polyamory. It is novelistic in intent. It explores the emotions of its characters dealing with complex changing situations, although at times it is pulled in the direction of memoir, where doing justice to actual events on occasion deprives the work of its full dramatic potential.

The work explores the intricacy of our emotions, the complexities of lived lives, the multi-determined nature of our beings. And what better way to push our emotional buttons than to take us deep into the realms of desire, jealousy and questions about the nature of love?

Having said that, polyamory is still at the heart of Double Happiness. In writing and discussions about polyamory and to some extent in this novel, we hear of the need to be honest with oneself and with those about one, to live without hidden agendas, suspicions, unhealthy desires, motivations and secrets which may lurk in dark spaces. We hear of care for others, exercising caution with emotions, the awareness of boundaries, acceptance of other perspectives, the fundamental principles of consent and mutual fulfilment. These are offered as the basis for building new forms of relationship to meet the challenges of monogamy head-on. And it is against these concepts that we can measure this novel.

Ten years later, in real life, the three main characters are still living in what seems to be a healthy fulfilling relationship. I loved seeing the three of them recently appearing on Compass, a television show on the Australian national broadcaster (ABC). https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-04-27/inside-lives-polyamory-ethical-non-monogamy-enm-ethics/105216136?

It seems that, despite the various travails of creating and maintaining non-monogamous relationships in modern-day Melbourne, Anna’s project to build an extended ‘family’ has succeeded. The program paints a picture of general happiness of Jeremy and Anna, Anna and Brendan and even, on occasion, of Jeremy and Anna and Brendan. Whatever awkwardness they felt (and I felt) was probably due to having cameras poked into their faces. Despite this they looked happy, the three of them. And at least one of them has found double happiness.